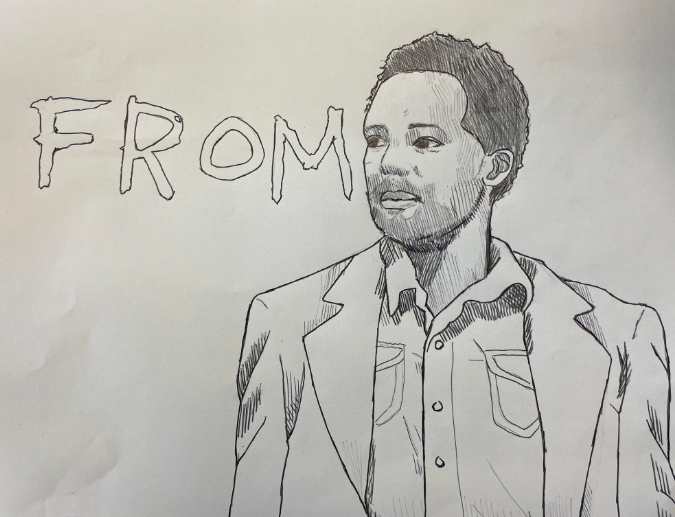

Jose Antonio Vargas is a journalist, filmmaker, and an immigration rights activist. This man is known as the face of undocumented immigration. His intellect and creativity is boundless and undefined by his status or the war that the US government has placed on his life.

His charisma and way with words reached the students of Mission’s 1st period, American Lit Honors class taught by our one and only Teacher Librarian, Ms. A. Students read his book, Dear America, Notes of an Undocumented Citizen, which shed light on the struggles undocumented immigrants face in the United States, a country with a long history of prejudice and hypocrisy when it comes to migration and other matters.

Vargas claimed, “Migration is the most humane thing.”

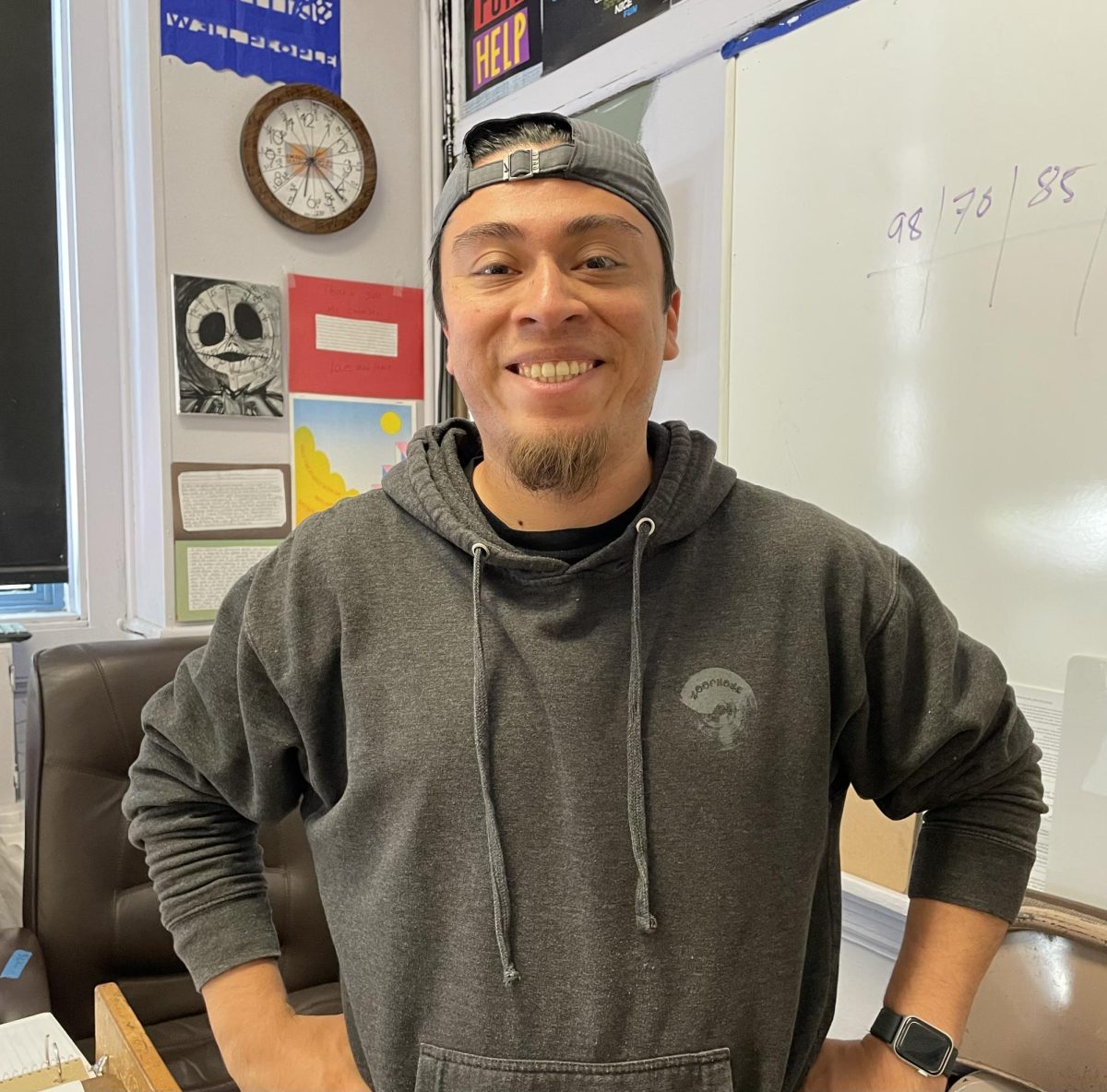

After spending a month and a half reading his book and writing about it, students met the man of the hour.

“America was like a class subject I’d never taken, and there was too much to learn, too much to study, too much to make sense of,” Vargas says in his book. When I read this part in class, I felt understood and related with him. That’s when I started to get into the book more.

I enjoyed hearing his experience of being undocumented. It was easy for me to relate to and not just an experience connected to my immigrant parents, but I related to it.

When I first came to America, I knew no English, and mostly just stared at other people. I wasn’t trying to be rude but everyone looked so different. I liked seeing how people’s beauty differed from one another.

At first, I went to a school with a bunch of other Hispanic kids who looked and talked like me. I felt like I belonged but not too soon after, I switched to another school where there were kids of many different ethnicities. I felt confused and out of place, not because I looked different, but because I could never understand what my peers were talking about.

Like Vargas who had many teachers and school administrators who took him under his wing, I got put into a class with a Spanish teacher who helped me out a lot. She’d teach me English and print my homework in Spanish. But she couldn’t help me much outside of the classroom. In the cafeteria where everyone had mac n cheese, pb and j sandwiches, or Lunchables, and I was heavily judged for my tortas and spinach quesadilla, a distinguishing green color. I never brought it back to school.

Reading Vargas’s work helped me find someone who I can relate to. As an undocumented immigrant, I’ve always wondered how I’m supposedly having more opportunity in the US, when I feel more restricted than ever.

Before I knew it, over the course of reading Vargas’s memoir, Jose Antonio Vargas became someone who inspires me, and most importantly, someone I look up to.

I was over the moon when I found out he was going to be coming to our class and I immediately offered to be one of the students to greet him. I got up extra early that day and even planned out how I’d talk to him. Unfortunately my shyness got in the way and I wasn’t able to get words out of my mouth.

I really wanted to thank him for sharing his story and tell him how brave he was for sharing his status to the world. In 2011, Vargas declared his undocumented status in the New York Times. There were so many things I wanted to say to him, but in the end I wasn’t able to.

When Jose started talking to the class I made sure to pay attention to everything he was saying. He talked about having a school named after him in Mountain View, where he grew up, and he also shared the possibility of his book becoming a musical, and his forthcoming book, White is Not a Country.

My classmate Alejandra asked if he regretted coming to America. Vargas hesitated, and eventually said, “Yes, I wish I had a mom.”

I was glad to see my classmates who were initially as interested in the book as captivated by this man as I was. Later, after his talk, I was lucky enough to get a copy of Vargas’s book signed and included in the picture. It was a really goood day.

*Esme is a pseudonym.